System Analysis

From Vengeance to Value: How Money Tamed the Blood Feud

// SYSTEM DIRECTORY

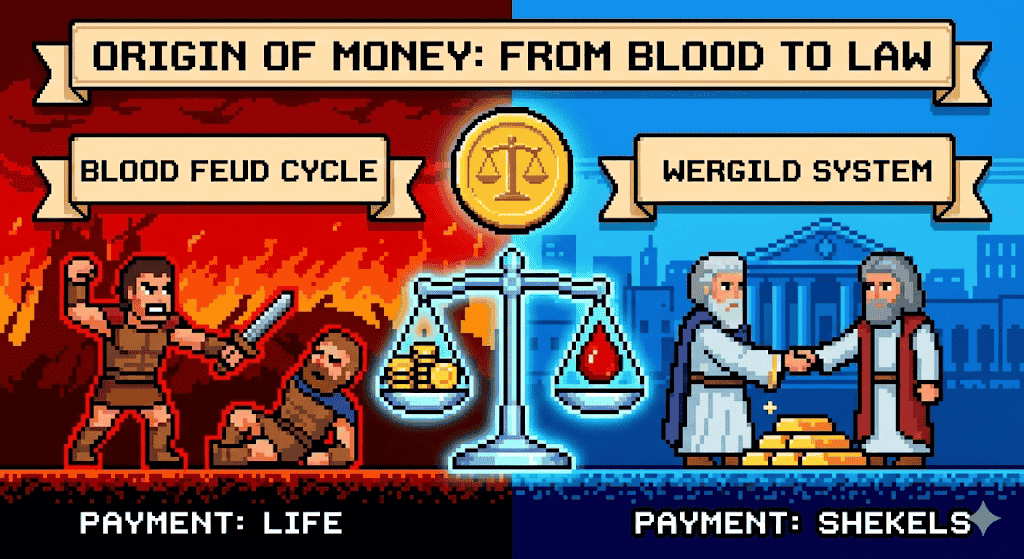

OPERATIONAL CONTEXT: Money did not originate merely for trade; it emerged as a mechanism for peace. In a world governed by "Blood for Blood," the invention of "Silver for Blood" was the technological breakthrough that allowed civilization to exist.

// SECTOR 01: THE INFINITE CYCLE

In early tribal societies, justice was personal. An injury (Death/Harm) created a debt that could only be paid in kind (*Lex Talionis*). The problem with this system is its lack of a "Stop Condition."

1. INJURY

Member of Clan A harms Clan B.

Member of Clan A harms Clan B.

→

2. VENGEANCE

Clan B kills Member of Clan A.

Clan B kills Member of Clan A.

→

3. NEW DEBT

Clan A now "owed" blood. Loop Repeats.

Clan A now "owed" blood. Loop Repeats.

SYSTEM ERROR:

Without a neutral medium of exchange, the "Exchange Rate" of violence is always subjective. Each side perceives their retaliation as justice and the enemy's retaliation as a new crime.

// SECTOR 02: THE INNOVATION (WERGILD)

The Mesopotamian legal codes (Hammurabi, Ur-Nammu) introduced a radical patch: **Restitution**. They quantified human damage into silver.

Wergild ("Man-Price"): The legal principle that every injury has a finite price. Once paid, the debt is cleared, and the feud is legally terminated. Money acts as a "Circuit Breaker" for violence.

Related: The Tyrian Shekel as Standard Value

Wergild ("Man-Price"): The legal principle that every injury has a finite price. Once paid, the debt is cleared, and the feud is legally terminated. Money acts as a "Circuit Breaker" for violence.

CIVILIZATION UPDATE:

By converting "Blood Debt" (Infinite/Emotional) into "Silver Debt" (Finite/Rational), society could finally achieve closure.

// SECTOR 03: THE PRICE OF A LIFE (DATA)

Ancient codes were specific. The value was determined by social status and severity of injury. While unequal by modern standards, the *existence* of a price list was a triumph of law over chaos.

BIBLICAL DATA POINT:

30 Shekels: The price of a slave (Exodus 21:32). This is the exact price paid to Judas for Jesus. Theologically, this signals that God paid the "Man-Price" for humanity's freedom.

// SECTOR 04: THE MODERN REGRESSION

Modern radical ideologies (Marxism, Critical Theory, Liberation Theology) represent a regression from the Wergild system back to the Blood Feud.

By defining justice as the rectification of "Historical Oppression" (an infinite, unpayable debt), they remove the possibility of settlement. If the debt cannot be paid, the only option is the destruction of the debtor.

System Analysis: Blood Feuds & The Modern Plaintiff

System Alert: The 10th Commandment Firewall

By defining justice as the rectification of "Historical Oppression" (an infinite, unpayable debt), they remove the possibility of settlement. If the debt cannot be paid, the only option is the destruction of the debtor.

SYSTEM WARNING:

The Rejection of Settlement:

Civilization requires that conflicts have an end. Ideologies that reject "payment" (reparations/reform) in favor of "revolution" (destruction) are effectively re-activating the tribal code of the Blood Feud. They prefer the purity of vengeance to the pragmatism of peace.

// SECTOR 05: THEOLOGICAL CORE

The Christian concept of **Redemption** (*Apolytrosis*) is economic. It literally means "to buy back" or "to pay a ransom."

The Gospel does not pretend the debt of sin doesn't exist (Moral Relativism). Nor does it demand the debtor bleed eternally (Blood Feud). Instead, it posits that the Wergild—the Man-Price—was paid by a third party.

Theological Context: The Second Creation

The Gospel does not pretend the debt of sin doesn't exist (Moral Relativism). Nor does it demand the debtor bleed eternally (Blood Feud). Instead, it posits that the Wergild—the Man-Price—was paid by a third party.

FINAL DIRECTIVE:

Christ is the "Redeemer" (The Payer). Satan is the "Accuser" (The Plaintiff). The ultimate victory of God is the settling of the account, ending the cosmic blood feud not by ignoring the law, but by fulfilling it.