I. Introduction and Methodological Constraints: Addressing the Fragmented Record

The reconstruction of Phoenician philosophy and cosmology presents significant challenges due to the nature of the surviving source material. Unlike the well-preserved texts of Greek thinkers, Phoenician intellectual traditions are primarily accessed through fragmentary accounts filtered by later foreign authors. The principal source for Phoenician cosmogony and social philosophy is the text attributed to Sanchuniathon, a purported ancient Phoenician sage. This work is known exclusively through fragments preserved by Philo of Byblos, who lived in the late first century AD and early second century AD.1 Philo’s compilation, described as a Phoenician *historia*, was less a true history and more an account of myths and legends, preserved mainly within the works of the Christian historian and theologian Eusebius (c. AD 260-340).1

The Filter of Transmission and Authenticity

The overwhelming modern consensus is that Philo of Byblos’ treatment of Sanchuniathon is highly mediated, representing a Hellenistic rationalized perspective, or perhaps even a deliberate literary invention, dating from the time of Alexander the Great through the first century BC.2 Philo employed Hellenistic terminology, for instance, translating the Phoenician supreme deity El as Kronos and Baal as Zeus.3 This conscious reframing served to present the Phoenician narratives in a structure intelligible and respectable to a Greek audience.

However, the analysis of this material reveals an authentic Canaanite core beneath the Hellenistic veneer. Archaeological discoveries at Ras-Shamra-Ugarit confirmed that Sanchuniathon’s cosmology contains an idiosyncratic version of native Canaanite mythology dating back to the second millennium BC.3 Key structural parallels exist, such as the struggle of Zeus-Demarous or Adodos (Baal/Hadad) against Pontos (Yam/Sea), and the retirement of Elos-Kronos (El) as an elder statesman to a *deus otiosus* role.3 The persistence of these deeply rooted mythic structures validates the claim that Phoenician materials formed the foundation of the text, even if Philo subsequently rationalized them for an intellectual audience.

The Intellectual Environment: Phoenician Proto-Science

The context in which Phoenician philosophy emerged—the 9th to 8th centuries BC—was defined by remarkable technological and economic prowess. Phoenicia was an early capitalist center, dominating world trade and demonstrating many features of a modern industrial society, including the prevalence of the secondary sector and the supremacy of merchant interests.4

The Phoenicians were recognized as being in the cultural vanguard, pioneering the phonetic alphabet, inventing concrete, and building advanced ships and multi-storied houses.4 Crucially, they were the birthplace of arithmetic defined as "the science of figures and measures," potentially originating the concept that reality could be founded upon number.4 Their intense focus on applied knowledge—in geography, mathematics, astronomy, physics, and meteorology—was unrivaled and predated that of their neighbors, including Egyptians, Babylonians, and Greeks. This knowledge conferred a strategic advantage, often referred to as a "monopoly on knowledge," which secured their commercial and political power.6

The intellectual climate favored natural philosophy, as Phoenician thinkers were the first to formally systematize it.4 The emphasis Philo placed on mechanistic, materialist principles in the cosmogony—such as Wind, Chaos, and Mot—was likely a deliberate amplification of genuine Phoenician foundational principles. This approach was intended to position Phoenician thought as the intellectual progenitor of Greek natural philosophers, thereby asserting the cultural priority of the Phoenician tradition.7

The inherent challenges of source criticism necessitate a cautious but critical approach, recognizing that while the language is Hellenistic, the core concepts detailed below represent sophisticated, materialist attempts to describe the origin and structure of the universe.

| Source Layer | Agent/Era | Nature of Contribution | Methodological Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Mythic Core | Canaanite/Ugaritic (2nd Millennium BC) | Core narrative structures (e.g., conflict myths, pantheon hierarchy). | Must be inferred through later parallel texts (Ugaritic Tablets).3 |

| Transmission Filter 1 | Philo of Byblos (Hellenistic Era) [1, 2] | Translation, editing, and rationalization using Greek philosophical vocabulary (e.g., Chaos, Pothos, Euhemerism). | Introduces potential distortion or complete invention of content.2 |

| Transmission Filter 2 | Eusebius (Christian Era) 1 | Selection and preservation of fragments for theological debate. | Introduces polemical bias; context often lost, content is sparse (approximately 20 pages of Greek).1 |

II. Phoenician Cosmogony: The Emergence of Order from Shapeless Matter

The Phoenician cosmogony, as recounted by Sanchuniathon, is distinctive for its materialistic explanation of the universe’s genesis, detailing a progression from an initial state of dynamic, shapeless matter to physical structure through natural mechanisms. This narrative shows significant affinities with Mesopotamian cosmogonies.8

The Primordial Dyad: Dark Wind and Gloomy Chaos

The foundational state of reality is described as a dualistic primordial dyad: "dark, windy air, or a wind of dark air, and turbid, gloomy chaos".8 These elements existed unboundedly for vast periods, lacking any defined termination.8 The conception of this origin emphasizes boundlessness and potential energy, distinct from simple void. The matter is characterized as "rude and undeveloped," a "shapeless heap" containing all discordant, confused elements.9

The Kinetic Principle: Desire (Pothos) and Generative Entanglement

The transition from chaos to creation requires an internal, non-theological mechanism. This mechanical cause is initiated when the elemental wind experiences an attraction toward its own beginnings, resulting in a physical "blending" or entanglement. This entanglement, a self-referential kinetic force, is designated Desire (Pothos).8

Desire is proclaimed as the "beginning of the foundation of everything." However, a crucial metaphysical distinction is made: this foundational mechanism did not "recognize its own foundation".8 The deployment of concepts suggesting sexual generation ("fell in love," blending) 7 within this materialist context signifies that the force driving creation is spontaneous, self-contained, and fundamentally unconscious. The entire cosmic process is thus dictated by inherent physical forces necessary for blending and generation, rather than intentional divine will. This elevation of unconscious, material dynamics to the status of a primary cosmic driver places this Phoenician system squarely within the tradition of early natural law, providing a proto-base for later materialist philosophies, including those of Ionian thinkers like Thales.7

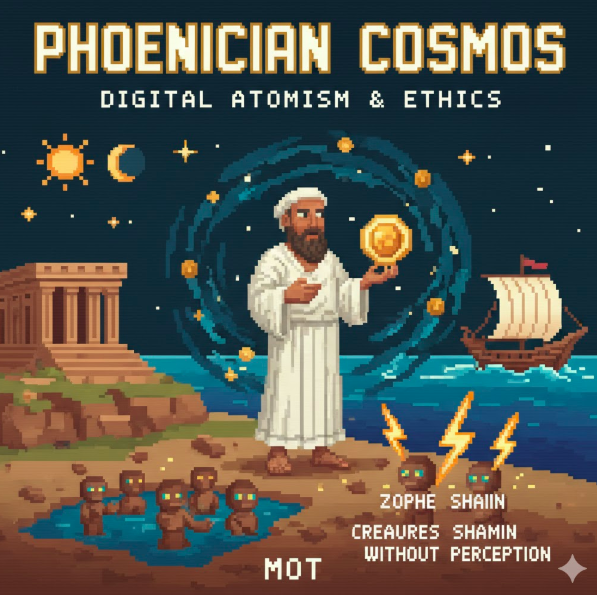

Mot and the Genesis of Material Substance

The generative entanglement of the wind results in the formation of **Mot**. This substance is defined variously as "mud" or "the ooze from a watery mixture".8 Mot is the universal progenitor, containing "the whole seed of creation and the genesis of all things".8

This cosmogony is predicated on the progressive evolution of matter. Life, in its earliest forms, is conceived as emerging directly from this moist silt.4 Mot, therefore, is the vital material link between pure chaos (wind and air) and structured reality, functioning as the coagulated, fertile substance from which the physical universe differentiates.

| Stage/Entity | Description | Metaphysical Role | Progression to Order |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Dark, Windy Air / Turbid Chaos" | The boundless, undifferentiated, and formless state. | Primeval substrate; source of kinetic potential. | State of potential entanglement. |

| Desire (Pothos) | The act of self-entanglement or blending of the primal Air. | The "unconscious, generative kinetic force." | Initiates material coagulation. |

| Mot | The resulting ooze, mud, or watery mixture. | The "whole seed of creation," material progenitor of the universe. | Becomes the cosmic structure (The Egg).8 |

| Heating/Collision | Differentiation via temperature and physical contact. | Physical law driving elemental separation. | Creation of sky, earth, sea, and elemental phenomena (thunder).8 |

III. Baseline Descriptions of Reality and Physical Cosmology

The Phoenician description of the cosmos moves beyond mythological accounts by incorporating processes derived from observation, defining reality through elemental differentiation and the mechanical origin of consciousness.

The Cosmic Egg and Elemental Differentiation

Once formed, Mot took on the shape of an egg.8 The subsequent structuring of the physical universe was achieved primarily through thermal and kinetic forces. The process of elemental differentiation began when the air separated and became distinct as a result of "heating." This mechanism led to the separation of the sea and the earth.8 From this separation arose secondary atmospheric phenomena, including winds, clouds, and "huge precipitations of the celestial waters".8

The celestial architecture involved the luminous bodies—the sun, moon, stars, and 'great stars'—shining out from Mot.8 While specific structural boundaries are not provided in the fragments, the overall cosmological description is comparable to wider Ancient Near Eastern models, where the universe is frequently conceived as a totality symbolized by the phrase "heaven and earth" or "heaven and underworld".10 Phoenician cosmology, however, distinguished itself by positing a system where the physical structure and celestial mechanisms were derived from proto-scientific principles rather than purely divine decree, reflecting the Phoenician reliance on advanced observational knowledge (mathematics, astronomy, meteorology).6

The Emergence of Percipient Life (Zophe shamin)

Sanchuniathon’s cosmogony details the development of life in progressive evolutionary stages. Mot initially produces living things that are "without perception," which subsequently evolve into creatures that possess perception.8 These sentient beings were designated **Zophe shamin**, or Watchers of the Sky.8

The final activation of consciousness in these percipient creatures is attributed to a violent, definitive physical event. This moment occurred when the elemental components, separated by heating, met and collided again, instantly producing "thunder and lightning." At the sound of the thunder, the percipient creatures were said to have "woke up." This awakening was paired with the stirring of the "male and female" principles on land and sea.8

The implication of this material catalysis is profound: awareness is postulated as an emergent property of complex matter reacting intensely to energetic physical phenomena. This perspective removes the necessity for a divine bestowal of consciousness and grounds sentience within physics, aligning with the highly applied, observational knowledge base for which the Phoenicians were renowned.6 The system establishes that existence begins with material self-organization, proceeds through elemental differentiation, and culminates in consciousness sparked by violent physical law.

IV. The Precept of Digital Atomism: Mochus of Sidon

One of the most enduring yet overlooked contributions of Phoenician thought is the atomic theory attributed to **Mochus of Sidon**, a proto-philosopher whose work provides a sophisticated synthesis of mathematics and physical ontology.

Mochus the Proto-Philosopher: Historical Attribution

Mochus (also known as Moschus the Phoenician) is listed by Diogenes Laërtius as a proto-philosopher.11 Ancient sources consistently credited him with immense antiquity and intellectual precedence. Strabo, citing Posidonius, definitively speaks of Mochus as the originator of the atomic theory, positioning him as more ancient than the Trojan War.11 This claim suggests that the foundations of atomism were established in the Near East well before the Ionian period. The ancient Greeks acknowledged this debt: Strabo recorded that the theory of the atom later promulgated by Democritus was actually of Phoenician origin, directly attributable to Mochus.12

This historical attribution was not lost on later Western scholarship. Prominent thinkers, including Isaac Newton, John Selden, and Ralph Cudworth, credited Mochus of Sidon as the original author of the atomic theory.12 This acknowledgment underscores the intellectual significance of Mochus’s model and its role as the undisputed antecedent to the later, more famous Greek atomism.

Defining Digital Atomism: Figures, Measures, and Numerical Ontology

The atomic theory developed by Mochus is hypothesized to be a form of **"digital atomism"**.4 This theory arose naturally from the Phoenician cultural milieu, which had pioneered arithmetic as "the science of figures and measures," potentially originating the concept that reality is inherently numerical.4

If the atoms are conceived as **"digital entities,"** they are not simply irreducible chunks of mass, but fundamental units defined by immutable mathematical or formal properties. This framework links the physical structure of reality directly to the abstract certainty of numbers and geometry, akin to the later Pythagorean tradition.4

The consequence of defining atoms as numerical entities is the assurance of metaphysical stability. Since numbers and figures are inherently unchangeable, equating the fundamental constituents of matter with these eternal properties ensures that reality, at its most basic level, remains permanent regardless of macroscopic alteration or decay. This ontological structure reflects the advanced state of Phoenician quantitative knowledge and served as a powerful philosophical mechanism for explaining the enduring nature of existence.

| Concept | Core Tenet | Associated Discipline | Historical Legacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomism (Mochus) | "Everything is composed of immutable, fundamental particles of matter." | Natural Philosophy / Physics | Credited as the first system of atomism, pre-Democritus. [11, 12] |

| Digital Atomism | "Atoms are comparable to unchangeable numerical entities, figures, or measures." | Arithmetic / Ontology | Links Phoenician calculation prowess to the idea of numerical reality, similar to Pythagoreanism.4 |

| Soul as Digital Entity | "The soul is an eternal, unchangeable digital unit." | Metaphysics / Theology | Provides philosophical justification for the soul's survival and persistence through reincarnation.4 |

The Digital Soul and Reincarnation

The application of digital atomism extends beyond mere physics into metaphysics, specifically addressing the nature of the soul. The mathematical stability inherent in the concept of digital entities provides the foundation for an unchangeable soul.

The theory suggests that the belief **"that reincarnation of souls as unchangeable digital entities is possible"** arises logically from the premise of digital atomism.4 If the soul is a digital entity, it possesses an eternal, formal integrity that renders it immune to the decay and transformation processes affecting non-digital matter. This mechanism resolves the philosophical challenge of persistence, ensuring the soul’s identity remains whole across multiple lifetimes, sustained by its foundation in immutable numerical principles.

V. Other Fundamental Precepts and Philosophical Legacy

The breadth of Phoenician philosophical contribution includes both rationalist social theory and the foundation of major Western ethical schools, reflecting a complex cultural and moral environment.

Sanchuniathon’s Rationalist Social Philosophy (Euhemerism)

Sanchuniathon is historically credited as the founder of social philosophy due to his rational theory regarding the genesis of religion.4 His system is largely **Euhemeristic**, proposing that gods were not original deities but either deified natural elements or, predominantly, powerful and accomplished mortals.4 These individuals—often former rulers or famous inventors responsible for cultural achievements—were rendered homage and subsequently deified after their deaths.4

Sanchuniathon viewed history primarily as a linear succession of cultural achievements and human inventions, such as the alphabet, seafaring, and the emergence of cities. He also articulated theories concerning an earlier matriarchal stage of human development.4 By reducing theological claims to sociological phenomena and historical events, Sanchuniathon provided a secular, rational explanation for societal structures and beliefs, mirroring the innovative, human-centric focus of the Phoenician trading culture.

The Foundational Ethical System: Phoenician Roots of Stoicism

Perhaps the most influential—though frequently anonymized—Phoenician contribution to Western philosophy is the founding of **Stoicism**. Zeno of Citium, born in the principal Phoenician city of Citium (Cyprus) in 333 BC, and his successor, Chrysippus of Soli, were both of Phoenician ancestry.13 Stoicism, emphasizing rigorous logic, ethics, and physics, came to dominate the intellectual landscape of the Hellenistic world and the Roman Empire, eventually influencing early Christianity.13

Zeno himself was initially a merchant before his dedication to philosophy, which reportedly began after a shipwreck diverted his life's path.13 The emergence of Stoicism, which prioritizes virtue, adherence to cosmic Logos (reason), and individual self-control, stands in stark contrast to the religious and ethical context of Zeno’s ancestry.

Historical accounts note a profound ethical duality within Phoenician society. While intellectually advanced, their mercantile culture was associated with notoriously abhorrent religious practices—specifically human sacrifice and sexual perversions tied to the worship of Baal and Astarte.14 These practices were intended as a form of **"mind-control and conditioning"** that effectively separated participants from universal moral laws, fostering a reputation for deceit.15

The development of Stoicism by Phoenician expatriates can be understood as an intellectual imperative to define a universal moral framework. Zeno’s system provided a definitive philosophy of virtue and self-mastery that was **diametrically opposed** to the localized, ritualistic, and ethically ambiguous practices of the Canaanite religious cults. Stoicism thus represented a powerful intellectual effort to transcend the moral failings of the ancestral culture and establish a global, rational ethical law applicable to all humanity.

VI. Conclusion: A Critical Assessment of Phoenician Intellectual Primes

The evidence affirms that Phoenician philosophical thought was not merely derivative of Greek systems, but constituted a highly developed, sophisticated, and materialist intellectual tradition that significantly predated and influenced the pre-Socratic thinkers.

The Phoenician cosmogony provided the earliest extensive model of creation driven by internal, material mechanisms. By positing a kinetic progression from dark chaos and windy air, through the mechanical force of Desire (Pothos), resulting in the material substance Mot, Sanchuniathon’s account established a proto-scientific system rooted in physics rather than theological creation. This focus on mechanism and elemental differentiation directly anticipated the core principles of Ionian Naturalism.

Mochus of Sidon’s atomism represents an equally profound contribution. The concept of "digital atomism" synthesized Phoenicia’s mastery of arithmetic with physical ontology, defining atoms as immutable digital entities. This framework established the numerical foundation of reality and provided a metaphysical justification for the persistence of the soul as an unchangeable digital unit, thereby resolving fundamental problems of permanence and identity. This quantitative approach influenced both subsequent atomic theory and numerical philosophies.

Finally, the philosophical heritage reveals a striking ethical dualism. While Phoenician commercial dominance was accompanied by morally catastrophic religious rituals, the intellectual response led to the foundation of the West’s most rigorous ethical system: Stoicism. The emergence of Zeno’s philosophy emphasizes the capacity of Phoenician thinkers to define a universal moral Logos that actively corrected the ethical vacuum of their own civilization.

In summation, Phoenician philosophical systems—characterized by materialistic cosmogony, quantitative atomism, and rationalist social analysis—demand re-integration into the narrative of ancient thought as a critical, advanced, and foundational intellectual power.

Works Cited

- PHILOF OF BYBLOS AND HIS " PHOENICIAN HISTORY -1 - Manchester Hive, accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.manchesterhive.com/downloadpdf/journals/bjrl/57/1/article-p17.pdf

- Sanchuniathon - Wikipedia, accessed November 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sanchuniathon

- 24. An Analysis of Sanchuniathon's Scheme in the Light of the Biblical Account (§§317-354), accessed November 5, 2025, https://www.christianhospitality.org/wp/6-days-creation24/

- Phoenician philosophy. - Румянцевский музей, accessed November 5, 2025, http://rummuseum.ru/portal/node/2491

- Финикийская философия и Библия. Открытие финикийцами Америки., accessed November 5, 2025, https://eprints.kname.edu.ua/11914/1/%D0%A4%D0%B8%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B0%D1%8F_%D1%84%D0%B8%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%81%D0%BE%D1%84%D0%B8%D1%8F_%D0%A0%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%81%D0%BE%D1%85%D0%B0.pdf

- Phoenician cosmology as a proto-base for Greek materialism, naturalist