System Analysis

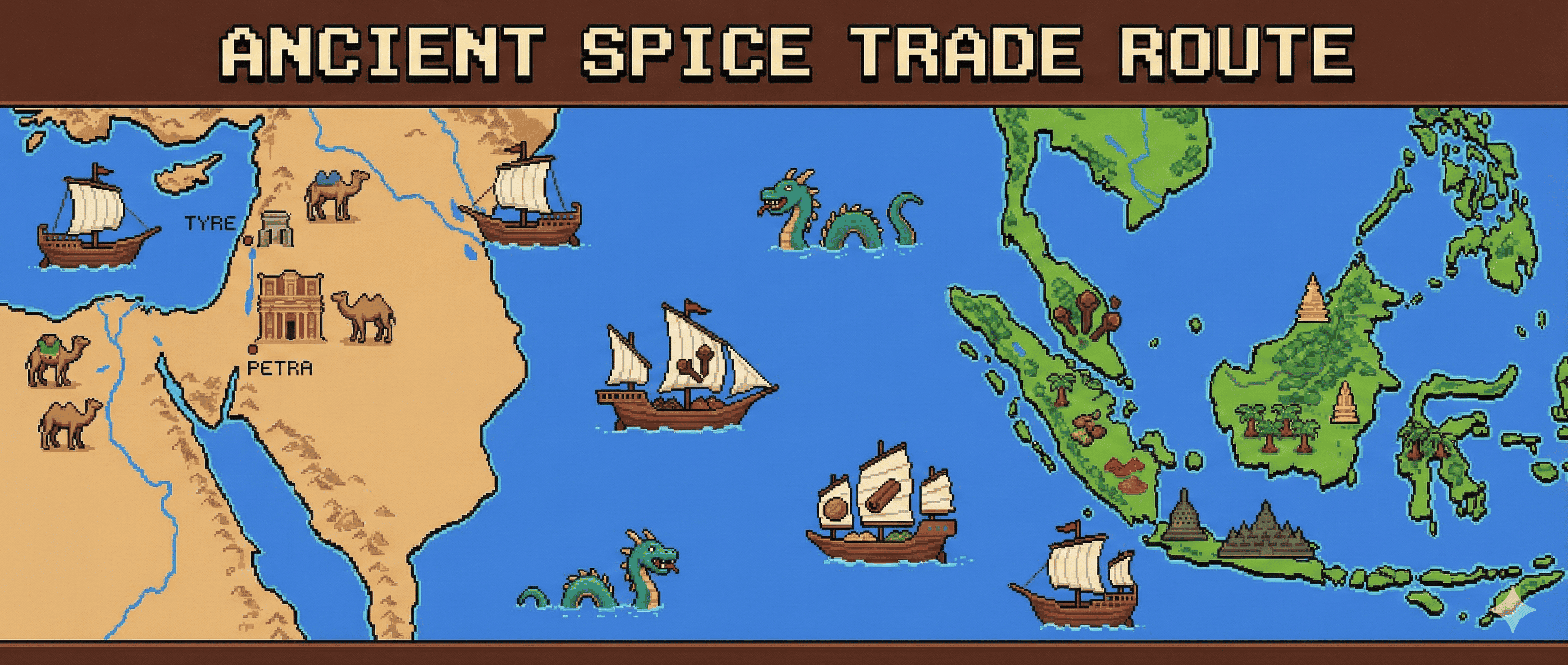

The Ocean Spice Trade: From Ancient Mystery to Global Routes

// SYSTEM DIRECTORY

OPERATIONAL CONTEXT: The persistent demand for oriental spices—particularly cinnamon, pepper, and cloves—was not merely a culinary preference. It was a geopolitical engine that drove the logic of empire, birthed the first megacorporations, and forced the discovery of the Americas.

Historical Context: The Phoenicians (Lords of the Sea)

// SECTOR 01: THE MYTHS OF ORIGIN

Arabian traders, who dominated the overland and maritime routes across the Red Sea, intentionally obscured the true origins of spices. They fabricated wild and terrifying myths to discourage outsiders from attempting direct access.

The Flying Snake Defense: Classical sources describe traders claiming cinnamon was harvested from deep gorges guarded by enormous, territorial birds, or that cassia grew in swamps infested with flying snakes. These were not superstitions; they were commercial barriers designed to protect price margins.

The Flying Snake Defense: Classical sources describe traders claiming cinnamon was harvested from deep gorges guarded by enormous, territorial birds, or that cassia grew in swamps infested with flying snakes. These were not superstitions; they were commercial barriers designed to protect price margins.

// SECTOR 02: THE ROMAN ERA

The Roman Empire's demand for spices eventually broke the Arabian monopoly. The turning point was the discovery of the Monsoon Winds (attributed to Hippalus, 1st Century AD). This allowed ships to bypass the coast and sail directly from Egypt to India.

System Architecture: The Pax Romana

ECONOMIC DRAIN:

Pliny the Elder famously lamented that Rome was draining its treasury to pay for Indian luxuries. This trade imbalance (Gold for Pepper) was an early form of globalized deficit.

// SECTOR 03: THE MEDIEVAL INTERREGNUM

With the fall of Rome and the rise of the Islamic Caliphates, the "Green Wall" descended. The trade routes were reorganized into a strict cartel. The Caliphates controlled the East; Venice controlled the West.

This monopoly forced prices sky-high in Europe, bleeding Christendom of its gold and creating the desperation that would drive the Age of Discovery.

Geopolitical Context: The Crucible of Conflict

This monopoly forced prices sky-high in Europe, bleeding Christendom of its gold and creating the desperation that would drive the Age of Discovery.

// SECTOR 04: THE AGE OF DISCOVERY

By the 15th century, the pressure was critical. Vasco da Gama's voyage to India (1498) and Columbus's attempt to go West were not scientific expeditions; they were desperate attempts to break the Venetian-Arab chokehold.

The Theological Pivot: As detailed in the Serpentine Protocol, this move to bypass the Islamic blockade inadvertently "Globalized the Gospel." The quest for pepper opened the door for the Great Commission to reach the Americas and Asia.

Grand Strategy: The Atlantic Breakout (Phase 06)

The Theological Pivot: As detailed in the Serpentine Protocol, this move to bypass the Islamic blockade inadvertently "Globalized the Gospel." The quest for pepper opened the door for the Great Commission to reach the Americas and Asia.

SYSTEM OUTCOME:

The breaking of the spice monopoly was the kinetic event that ended the Middle Ages and launched the Modern Era. It shifted the center of world power from the Mediterranean (Venice/Constantinople) to the Atlantic (London/Lisbon/Amsterdam).

// SECTOR 05: THE CORPORATE ERA (VOC)

The risks of the spice trade were too high for individuals. Ships sank; crews died. To manage this risk, the Dutch invented the **Joint-Stock Company** (The VOC). This allowed risk to be distributed among thousands of investors, birthing the modern stock market.

The Manhattan Swap: The value of spices was so extreme that in 1667 (Treaty of Breda), the Dutch happily traded their colony of **New Amsterdam (Manhattan)** to the British in exchange for the tiny island of **Run** in Indonesia—the world's only source of nutmeg. They traded the future capital of the world for a spice monopoly.

The Manhattan Swap: The value of spices was so extreme that in 1667 (Treaty of Breda), the Dutch happily traded their colony of **New Amsterdam (Manhattan)** to the British in exchange for the tiny island of **Run** in Indonesia—the world's only source of nutmeg. They traded the future capital of the world for a spice monopoly.

HISTORICAL IRONY:

The Dutch won the trade (getting the nutmeg), but the British won history (getting New York). This illustrates how "Resource Curse" can blind empires to long-term strategic value.